Explorers push boundaries in their return to the frozen continent, uncovering the untamed beauty of Antarctica.

At the beginning of the year Bethan Davies and crew spent a few months on James Ross Island, Antarctica. Well they are due to head back again in 2012. You can catch the first report of their time out there. Antarctica #1 If you’ve ever wondered what they get up to when back, Bethan sums up some follow up work going on through the summer.

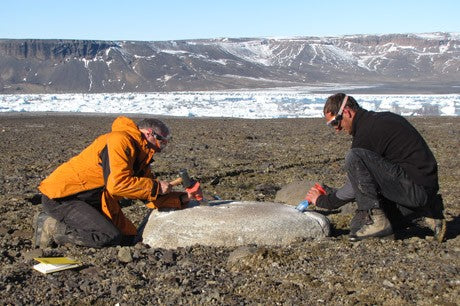

We have been awarded a second field season! This is because we were unable to get good geographical coverage during our first field season. We were restricted because BAS and the Royal Navy no longer have helicopters, so we were restricted to just one field camp. So, in January, the Royal Navy on their new ship, HMS Protector, will be taking us to Terrapin Hill on James Ross Island. Of course, this is still in the planning stages and anything could happen, but we are rushing around to try and get ready! First, we want to finish writing up and publish results from our first field season. Things are happening quickly now and we are rushing around in a blur of packing and shipping deadlines, medicals, dental examinations and training courses. This year, the team will be myself (Bethan Davies), Professor Mike Hambrey and Professor John Smellie, plus a field assistant. Our tasks are similar to before – to create a geomorphological map and to sample erratic boulders for cosmogenic nuclide dating. Of course, it’s never 100 % certain until you’re actually on the island - Cross fingers for our second field season!

We have submitted and been awarded a grant to fund cosmogenic nuclide dating of granite boulders that we sampled during our last season to James Ross Island. The quartz crystals in granite boulders interact with cosmic rays from space; these cosmic rays cause changes in various isotopes in the rock crystals. By measuring the radioactive decay of some of these isotopes, we can establish how long the granites on James Ross Island have been exposed – thus dating the recession of the Antarctic ice Sheet at the Last Glacial Maximum. Terrestrial dates like these are important in Antarctica; ice-free areas are rare (less than 0.2 % of the total land area), and most of the dates from Antarctica are derived from radiocarbon dates from marine organisms.

This new data will help us to get a better understanding of ice sheet mechanisms and mechanics, and how in the past it interacted with climate change. By working with scientists in the modelling, biology, atmospheric science and ice core chemistry fields, we will eventually be able to put together a holistic model of the past Antarctic Ice Sheet, which will inform future projections of melting, sea level rise and climate change. And so I’ll be spending September in East Kilbride at the NERC lab, doing sample preparation and analysis to get 30 cosmogenic nuclide dates from granite erratic boulders from James Ross Island.

I went to Edinburgh for the XI ISAES conference, which was held in Pollock Halls of the University. There was an excellent welcome event held in Dynamic Earth hall, which I highly recommend!

The conference was an opportunity to meet people working on all aspects of Antarctic Earth Sciences, and was well represented by people from the newly established Korean Antarctic Programme, Japan, America, New Zealand, Europe and Australia. It was an opportunity to meet many famous people, and to listen to the latest scientific developments. Some of the talks got me very excited, and I have returned home, fizzing with ideas for interpreting some of the strange landforms we saw on James Ross Island on our last fieldwork. Of course we were proud to have an Alpkit logo on our posters!

One of the most interesting talks was by Professor Jane Francis of Leeds University, who used art and illustrations to great effect in her presentation, looking at the evolution of the Antarctic continent through time. Other interesting presentations showed how you could use biodiversity and refugia as a means to work out where ice-free areas were during the last glacial maximum in Antarctica. The location of these oases is very important to modellers, who need geological data to provide vertical constraints on their ice sheet models.

An exciting development over the last few years is the increasing interaction and collaboration between geoscientists and modellers. These people use computer programmes to try and recreate the Antarctic Ice Sheet over millennia. Once they have a good fit to the geological data they can have confidence in these models, and use them to predict the future behaviour of the ice sheet. They are also excellent for setting up and testing hypotheses, and identifying new areas for research. Our data from James Ross Island will help mathematical modellers to create more realistic reconstructions of the last Antarctic Ice Sheet.