Antarctic Diaries 2012: Adventures in the icy wilderness of Antarctica.

Friday 17th February 2012

On board the Ship

This morning the team set sail en route to Antarctica. This is the first season south for the new ice breaker to Antarctic waters and she has been fitted an echo-sounder and the helicopter flight deck has been moved aft, which is the ice position. Painted bright red and white, it will be in stark contrast to the ice once we are underway. The team are now bracing themselves for the rough waters of Drake Passage, and have all stocked up on sea sickness pills. Whales have already been spotted from the Bridge, along with shags and albatross.

The scientists have been furnished with comfortable, compact cabins, and were invited to relax with the officers in the Ward Room. The officers have been extremely welcoming and friendly, and invited us to dine with them at the comfortable Officer’s Mess. We had a few drinks with them on the first night when alongside.

Whilst we have been accommodated on board, we have been sorting kit and checking equipment. Everything seems to have survived the long ship’s passage South, and we have assembled and checked the rocksaw and Alpkit Heksa Basecamp tent This should make it easier to put up once onshore, which should happen Monday or Tuesday.

Because of poor satellite communications and lack of internet, I will be unable to send this blog out until I return to the base; therefore I will keep it as a diary and Alpkit will get the full blog upon my return to civilisation!

Esperanza base

Thursday 23rd February

On board the Ship

The Ship made good progress across Drake Passage, before visiting Esperanza, an Argentinean base at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, for an informal visit. By Thursday, the team are still onboard, having tried and failed to enter Prince Gustav Channel. The strong southerly winds that slowed the ship down on its journey south across Drake Passage had blown thick sea ice as far north as Joinville Island. With sea ice at ten tenths (if the sea is divided into a grid of ten squares, all of them have thick ice in), no ice breaker would be able to break the ice and pass through.

Prince Gustav Channel

There was nothing to do but head North to Elephant Island, South Shetland Islands, for the ship’s hydrographers to complete some outstanding tide gauge and swath bathymetry work (mapping the sea floor) using the SMB (Survey Motor Boat) James Caird VI, and wait to see if the ice would clear.

Point Wild, Elephant Island, is the site where some of Shackleton’s men were left to wait in a small upturned wooden boat. Having been enclosed in pack ice in the Weddell Sea, the Endurance finally sank in the northern Weddell Sea on November 21st, 1915. Shackleton’s men set up camp using lifeboats on the pack ice, before launching the small lifeboats north of Antarctic Sound once they were clear of the pack ice on April 9th, and sailed for Elephant Island. Here, Shackleton left Frank Wild in charge before heading for the whaling stations on South Georgia on April 24th, 1916, in the James Caird. Captain Wild and his team made camp on a small promontory of rock on Elephant Island, trapped between vertical cliffs and two impassable glaciers. There were surrounded by penguins and sea lions. Half starved, frost bitten and exhausted, the men waited four months for Shackleton to return.

The Captain arranged for the ship’s company to visit Point Wild whilst hydrographic surveying was being undertaken. This opportunity was relished by the BAS scientists and by Iain Rudkin (“Cheese”), the field assistant assigned to our project. Relieved at the prospect of getting off the ship, even if only briefly, the team gingerly clambered down a rope ladder into a speed boat waiting at the bottom. This effected a fast and rapid transfer to a small Zodiac (a RIB) closer to the bay. En route, we stopped to watch whales breaching and fluking nearby.

Point Wild is a tiny scrap of rock, and living there for months on end with nothing to eat but penguins is unimaginable. The clamour and smell of the penguins reached us from the point well before we reached there with our little boat. Once there, we were given free-reign to wander amongst the Chinstrap colony.

The penguins were moulting, the chicks nearly fully grown, with many half-fluffy chicks. There was one lonely juvenile King penguin, and several sheathbills. To wander amongst them, in such a historic place, was truly a privilege.

The ship’s surveyors will continue their tide gauge and swath bathymetry work for the next 24 hours. Then we will sail south again to James Ross Island, and see if we can penetrate Prince Gustav Channel. In the meantime, there is little to do but watch the whales nearby, and to try to catch that elusive fluking tail shot.

Saturday 25th February

On board the ship.

Last night the ship again ran into a wall of ice in Antarctic Sound and had to turn back north again. The most recently acquired satellite radar image shows that the area is choked with solid pack ice and is impenetrable. The ship’s company therefore decided to sail to King George Island to recover a tide gauge, before heading to Deception Island for two days of hydrographic surveying and levelling. We are hoping that the westerly gales forecast for Sunday will clear the pack ice from Antarctic Sound, allowing us passage to James Ross Island on Tuesday. In the meantime, humpback whales are breaching nearby, and we all spent a while on the upper deck, trying to photograph their dramatic breaches.

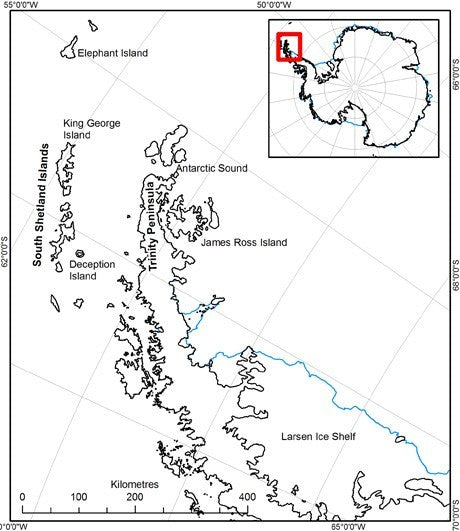

Location Map. Showing the main visiting spots of Elephant Island, Deception Island, Antarctic Sound and James Ross Island.

Sunday 26th February

On board the ship.

Whilst sailing to Deception Island yesterday, smoke was spotted on King George Island from the bridge. Contact with Jubany Station indicated that there had been a fire at the Brazilian base, Comandante Ferraz, in Admiralty Bay. We sailed directly into Admiralty Bay to offer any assistance possible. Upon arrival, we found that all personnel had been evacuated, but tragically there had been two fatalities. However, the fire was still burning, dangerously close to a fuel depot. The ship’s company therefore spent most of yesterday successfully fighting the fire.

The plan for today is to remain in the area throughout the day with a Sunday routine, which means a relaxed day for the sailors, who are all tired after a busy day yesterday fire-fighting. We sail to Deception Island overnight for two days hydrographic work, and then hopefully on to James Ross Island. We are worried about the weather; this time last year we were mostly confined to our tents with bad weather, so even if we get to James Ross Island, we may be unable to do any work.

Whalers Bay - Deception Island

Monday 27th February

On board the ship.

This morning we sailed into the natural harbour of Deception Island. It was grey and snowy and miserable, so unfortunately there was little to see. Deception Island is the crater of a caldera volcano. It is approximately circular, with a narrow opening through which ships can pass. As we passed very close to Cathedral Crags, the hydrographers were busy keeping an eye on rock spikes below the sea surface, which are the remnants of volcanic vents. We are now in Dynamic Positioning mode near an abandoned British research base (‘Base B’) an old Norwegian whaling station in the appropriately named Whaler’s Bay). Many of the beaches around Deception Island are volcanically heated, with curtains of steam forming above them at low tide. Typically these beaches are 20-40°C, but a few fumaroles are super-heated to 103-107°C. The volcano was particularly active during the nineteenth century, with eruptions in most decades, but there were only two periods of eruptions during the twentieth century. Deception Island volcano will almost certainly erupt again.

Human occupation began on Deception Island from 1820, as a sealers’ harbour, and later as a base for whaling ships. Deception Island played an important role in the Second World War during Operation Tabarin in 1944. This project was designed to destroy the abandoned stocks of coal and whale oil in the whaling station, so that German raiders could not refuel. At the same time, they built a new base for British scientists, called ‘Base B’. This re-established British presence in Antarctica in support of the UK’s claim to territory. Base B was occupied continuously until the first eruption in 1967. It was severely damaged by floods related to another eruption in 1969, and was subsequently abandoned.

The aim is to remain here for two days, to allow the hydrographers to collect tidal data. Then it is back to James Ross Island for a third and final attempt at deployment on Thursday.

Wednesday 29th February

On board the ship

It is 1300 and we are about the leave the natural harbour of Deception Island. We have sat here for two days but high winds prevented anyone from leaving the ship. The Bridge is on ‘Specials’ with many sailors keeping watch in all directions, and all wearing their white caps. We aim to reach Antarctic Sound by midnight and to overnight at Esperanza again, before finally having one more attempt at reaching James Ross Island. The wind within the harbour is currently 40 knots and higher winds are expected once we leave Deception Island; Sea State 7 is anticipated for the crossing.

This morning I followed the Engineering Officer (“Engines” or Phil) on his rounds. We saw all the mechanical workings in the ship’s underbelly, and the safety features to prevent a flood or fire in the engine room. They include extra pumps and a new separate generator in case the generators in the engine room fail. I climbed up and down hundreds of steep ladders, climbing from the bottom of the ship to all the way up inside the crane and down and up again. These ladders must keep the engineers fit! The engine room and generators were spotless and sparkling, with not a spot of grease to be seen. Shipshape indeed.

Having completed the work we brought for the journey, read all our books and watched all our films, the team are frustrated, and cannot wait to get ashore tomorrow. Iain (“Cheese”, the field assistant) is particularly fed up, having been on board since January 1st. With luck we will get ashore tomorrow and get 6 days fieldwork. The tedious monotony of two weeks at sea is really beginning to bite.

Thursday 1st March

On board the ship

14.30

This morning we awoke to grey cloudy skies near Hope Bay and began our transit towards Prince Gustav Channel. The radar image suggested that Fridjtof Sound was clear, and we began to pick our way through. The numbers of icebergs steadily increased, and many had fur seals or Adelie penguins sat on them. Perfect hunting ground for orcas, but unfortunately none were to be seen today. As we approached Vega Island and James Ross Island was sighted in the distance, the pack ice density increased and ice breaking began in earnest.

The team spent much time on the bridge or foc’sle, watching the prow of the ship cutting through the ice. Many times the ship came to a complete halt, and we were forced to reverse and try again. As our speed has decreased, we are now hoping to reach Croft Bay late tonight, and with luck will be put ashore before dark. We are packed and ready to go at a moment’s notice.

Later…

After much difficulty, James Ross Island was sighted and we entered Croft Bay. I was asked to go into the speed boat with an officer and two boatmen, to identify our campsite and see if it was feasible to be put ashore. The ice was a maze, and many times we were turned back by the thick pack ice. Terrapin Hill was in sight, and I was worried that having come so close, we would be unable to get ashore.

However, we finally found a way through. Close to the bay, the sea surface was starting to freeze, and the beach was covered with bergy bits. As it was getting late, the officer recommended that we be put ashore first thing in the morning. While we were waiting to be hoisted back aboard, I was allowed to drive the speedboat.

When we got back to ship, the Captain decided that we should go ashore straight away, so that we could have a full day of fieldwork tomorrow. With the sea ice continuing to close in, the ship would stay nearby, ready to scoop us up at a moment’s notice. We had to rush to get ready, and by the time I was hoisted back aboard, the crew had already loaded our kit into bags for winching onto the landing craft. By 10 pm (and still without dinner), we had the tents up and water boiling for our ration packs.

Friday 2nd March

Terrapin Hill

This morning, excited to be finally ashore, we rose early and got the water boiling for our porridge. We had some jerry cans of ship’s water, but they had started to freeze, so this took a while! Brushing my teeth was the next challenge, as my toothpaste had frozen in its tube. Getting ready for fieldwork took a little longer on this first day, as we found our science kit and sorted our bags.

Looking down to basecamp

Our plan was to walk to the top of Terrapin Hill, and collect rock samples on the way down. To aid rapid sampling of tough granites, we had a rock saw. Sadly this failed to start up, and despite taking it apart and putting it together again, it was a lost cause.

The weather was foggy and misty, so unfortunately views were limited. We did not allow this to dampen our spirits though, and set off for our march to the top of the hill, stopping to make notes and observations along the way. We found a large granite boulder at the summit, perfect for sampling. For the first time, Cheese and John got to sample the joys of rock sampling with a hammer and chisel.

Half way up Terrapin Hill we found Hideaway Lake, a gash cut into the hillside. Not visible from below or above, it comes as a surprise when you almost fall into it. One of our objectives is to try and understand how this outstanding natural feature was formed.

We returned to camp about 7 pm, boiled water for tea and dinner, and fell exhausted into bed after a productive day, despite the setbacks and weather.

Terrapin Hill

Saturday 3rd March

Terrapin Hill

It snowed heavily overnight, and much of the ground was obscured, making mapping difficult. However, we had photographed suitable boulders the day before, and set off back to halfway up Terrapin Hill, to continue our transect down. We managed to sample five boulders today, an impressive achievement. We returned to camp about 6, all rather chilly from walking in cold, windy, foggy weather all day. By 9 pm we are all tucked up in bed, me with my luxury item: a hot water bottle.

Sunday 4th March

Terrapin Hill

The snow that fell on Friday night had begun to thaw and get blown away, so despite the persistent low cloud, the weather was better today. We had planned a walk around the perimeter of our valley, and set off early to complete our task. During the afternoon, the sun broke through the cloud, allowing a few shafts of sunshine to reach us.

In Boulder Valley, we found an amphitheatre filled with soft sandstone concretions, beautifully weathered by the wind. Delicate protuberances, filled with holes, stand out vividly against the orange volcanic rock called tuff. As the weather began to slightly improve, we had beautiful views across the valley, to the top of Terrapin Hill and across to “Cascade Glacier”.

Cheese delights in rock sampling with hammer and chisel

Ventifact. wind sculpted boulder

As we returned to camp after a fruitful third day’s fieldwork, we planned our itinerary for the next few days. That night, the wind began to get up and we went to sleep, listening to it howling outside.

Monday 5th March

Terrapin Hill

We awoke this morning to a howling gale and the sound of snow being hurled against the tent. So we turned over and went back to sleep. By 8.30, the wind began to lessen, so we ventured out to our Alpkit tent for breakfast. As the jerry cans had frozen even more overnight, getting the water boiled was a major undertaking!

We had our sked (scheduled radio broadcast) with Rothera around 9.30, and spoke to the ship afterwards. By this time, the weather had calmed enough that we were ready to go out and work for the day. Unfortunately, the ship’s Captain had received another weather forecast and satellite image of the sea ice. It seemed that the gales the night before had blown more ice north, and we were in imminent danger of becoming trapped on James Ross Island. We were to be ready to be uplifted by 5 pm. Knowing that we had only a few hours of precious fieldwork left, we set off immediately to complete our sampling. Cheese left after lunch to begin striking camp whilst the scientists (or ‘beakers’) continued to work.

Mike finds a good rock…

At 4 pm we returned to camp to take down the tents and pack our kit away. We worked hard during our 3.5 days of fieldwork and achieved a lot, but we were all bitterly disappointed to be going home after such a short season.

By 7 pm, we were showered and eating dinner in the mess on board the ship. As soon as we were aboard, the ship began to sail for Frijtdof Channel, and was immediately forced to begin ice breaking. The next 24 hours were very difficult for our excellent crew, as they were forced to break ice through the night. We were immensely grateful that they had allowed us the extra half day’s work ashore, as we knew how difficult ice breaking at night was. By the time we were eating dinner, the ship was jolting and creaking as it broke ice.

Tuesday 6th March

On board the ship

The ship reached safer environs overnight, and now set sail for Greenwich Island, South Shetland Islands. A base visit is planned, along with some important engine repair work. We are set to return to base on the 14th of March, and should be home by the 17th. En route, there is a planned stop to the Chilean Base Prat, Greenwich Island.

Wednesday 7th March

Base Prat, Greenwich Island

Today we were entertained by the Chileans when the ship’s company visited Base Prat. This entertainment comprised a football tournament (decisively won by the Chileans), a BBQ, tours, dinner, wine…

Mike and I received a personal tour from one of the sergeants, which included the small Gentoo colony on the island. I have now seen King, Gentoo, Adelie, Chinstrap and Magellenic penguins during my two seasons – my mission to see them all is gathering pace!

And finally a couple of nice shots of the Heksa tentat basecamp from Iain Rudkin.